“I leave nobody behind. They are all before me still. I must advance.”

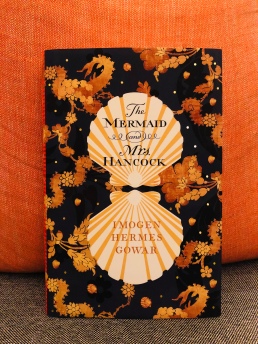

A review of The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar

Harvill Secker, 496 pp, £12.99, Jan 2018, ISBN 9781911215721

“I have tried to show how all these people share, and all these books and environments express, certain distinctively modern concerns. They are moved at once by a will to change-to transform both themselves and their world-and by a terror of disorientation and disintegration, of life falling apart. They all know the thrill and the dread of a world in which “all that is solid melts into air.”…

…the idea that the daily routine of playgrounds and bicycles, of shopping and eating and cleaning up, of ordinary hugs and kisses, may be not only infinitely joyous and beautiful but also infinitely precarious and fragile; that it may take desperate and heroic struggles to sustain this life, and sometimes we lose.”

– Marshall Berman, All That Is Solid Melts into Air

While I was reading The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock, I had a nagging feeling at the back of my mind; as if there was something going on that I couldn’t quite grasp. As I drew closer to the end, these vague ideas began to coalesce into a more solid conception of what this novel was trying to say behind its surface, and I immediately thought of these words from the preface of Berman’s seminal text on modernity.

Until about halfway through this novel, I confess, I did not understand why it had been touted as one of the most anticipated debut novels of 2018. I could appreciate the detailed reproduction of the language and culture of its Georgian setting, words like ‘sopha’ and ‘cit’ and ‘nunnery’ cropping up in the pages as well as a rather amusing reproduction of the “baby talk and garbled vowels” of certain upper-class gentlemen, and its deliberate distancing from the stately (and boring) mansion and ballrooms of period drama; but it felt to me a bit aimless and meandering.

One’s first impression of The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock is that it will be something of a fairy-tale. With the word ‘mermaid’ in the title, how could it not be? This is an assumption supported by the gorgeous cover art, all midnight blue and gold with curly lettering and shiny embellishments. Taken alongside the vintage-look title page and division of the text into three ‘volumes’, it appears as if the book is attempting to convince the reader they are not only reading a novel set in the late 18th century, but that it could have been plucked off the shelf in 1785.

Recently while browsing in bookshops, I’ve noticed an upsurge in lavish and intricately illustrated covers, with this novel following the likes of last year’s The Essex Serpent, but I’m certainly not complaining (although my bank balance might).

My impression of this fairy-tale aesthetic continued throughout the initial pages, as we are introduced to Mr Hancock surrounded by counting-houses and cats and crows, to Angelica Neal, a beautiful young woman with long golden hair, and an old woman with a wart on her lip who speaks of spirits and ominously warns Mr Hancock that “change is coming”. A confectioner’s shop appears as a fairy-land of shimmering sugar sculptures, jewel-like millefruits and a fruit display which is more like an orchard overflowing with an almost cartoonish abundance of nature:

“peaches and plums ripe to bursting…melons breathing their musk out in great waves”

This is a world which deserves a mermaid; the mermaid of myth and legend with perfect female hair and face and breasts atop a beautiful blue-green scaly tail.

Alas, this is not the mermaid we get.

In perhaps what is our first sign that this glittering world is not all that it appears, the actual mermaid brought by Captain Jones to Mr Hancock’s door is compared first to a “brown and wizened” old apple, and then to “long-dead rats” whose skin crumble at the slightest pressure. Hardly the lovely and vibrant creature of mythology. But it cannot be wholly dismissed as a monster; and indeed, this small creature becomes an inexplicable source of pathos through the evocation of its emaciated form and little fists held up to its face like any other infant.

This is the mermaid which leads to the collision of two worlds; that of the respectable middle-class, suburb-dwelling merchant Mr Hancock and his household, and the sphere of a certain calibre of prostitute and their genteel clients, represented by the effervescent Angelica Neal and the girls of the ‘nunnery’ kept by her former employer, Mrs Chappell.

This is initially an uneasy meeting, with disdain and miscommunication on both sides as the two parties are unable to understand the London that the other inhabits.

The novel presents the lives of Mr Hancock and Angelica as a collection of intimate details: business-like dealings between prostitutes and madams couched in the language of commodities, petty insults and arguments between the girls, quiet comradeship, afternoon tea, an orgy, men’s hair beneath their wigs, chamberpots in carriages. Sex, violence, and the degradation of figures of power. Not the stuff of our sugar-coated fairy-tale picture of history.

Talking of an un-idealised portrait of history, there is no attempt to shy away from the facts of Empire and Colonialism and Slavery, and everything else which makes possible this veneer of pleasure and ease. For instance, one of Mrs Chappell’s girls is Miss Polly Campbell, “a tall and lovely mulatto girl of about seventeen”. Polly struggles with self-identification in the face of the multitude of categorisations which are pushed onto her by others; her varying statuses as a mixed-race outsider, the cherished child of a plantation owner and his favoured slave-woman, and as a ‘fallen woman’. She is one of the most interesting and unique characters I have encountered, and could have been the sole protagonist of another book.

Good historical fiction foregrounds the details of small and inconsequential lives against the immense backdrop of History with a capital ‘H’, and demonstrates how its tendrils inevitably touch these individuals, which certainly works to powerful effect in Gowar’s novel. There are no abolitionists on soapboxes, nor slaves toiling on the Southern plantations. Instead, the debate around the government’s treatment of freed slaves is presented through the lens of an idle chat over newspapers and afternoon tea in Angelica Neal’s rooms in London, in a way which attempts to capture how ordinary members of the public felt about these issues.

This approach is, however, limited by the fact that this strand of the narrative, a hugely important part of British history which is often glossed over, has to vie for prominence with everything else that’s going on. I understand it is meant to highlight the tangential place occupied by wider issues in the lives of most people, in the same way people read the Sunday newspapers today, but it felt slightly shallow.

If I have one major criticism of Gowar’s novel it is this: that it takes on a great deal in its sprawling and expansive exploration of class and power and sexuality and race, and largely succeeds, but several significant elements do inevitably fall by the wayside and are only unsatisfactorily touched on.

However, I was finally able to unite these disparate and bitty elements into a larger and more coherent reading which opened some intriguing possibilities. In this novel, Gowar is clearly exploring the impact of ‘modernisation’, but in a manner centred around the domestic and mundane; all of the little details of the novel are like arrows emerging from the central, nebulous concept of a new society which is still under construction by those in power. The innovation of the novel is its focus on those who are not “protected by webs of property and connection”, single and poor women who are perceived as “near as well a whore, even if [they] have not fallen yet”.

Nothing is certain, everything is shifting, nothing is clean. Everyone in Gowar’s novel has “a will to change” battling with their “terror of disorientation and disintegration”, as Berman so neatly expresses. This is a world which is evolving, in ways which are evident from the beginning to the end of the novel. As well as the diversification of England’s cultural landscape, there is a “new kind of intimidation” of black servants utilising cool politeness to keep visitors in check, the factory workers are unionising, and Mr Hancock is eager to break out of his inherited position and seize the riches and success offered by his mermaid.

And yet, the advent of this period also begs the question: if this is a time of opportunity and advancement for men, what is it for women? This is the question which The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock attempts to answer; to portray women who exist outside of essentialising categorisations like ‘innocent victim’ and ‘respectable matron’, and who also want more.

The decreasing fortunes of Mrs Chappell, and her gruesome fate, epitomises the crucial idea that there are always casualties of ‘progress’, and that these casualties are inevitably those who belong to those marginalised groups in society- women, the poor, and racial minorities. This is a sentiment which is especially resonant in this current moment, given the tense and uncertain political and social climate, both in Britain post-Brexit and worldwide. It is a sharp reminder of the violence of change, and a warning of the hypocritical urge of those in power to identify and scapegoat the ‘other’, in this case the “monstrous bawd” who defiles innocent girls, in their desire to somehow wipe away and rewrite the past.

The mob want to see justice done, and she is easily within their reach.

Throughout the novel, both Angelica and Mr Hancock are yearning for something more in their lives. All of the domestic arrangements established in the first half of the narrative are slightly off-kilter. Mr Hancock constantly sees the ghost of his son as the child and young man he never had the opportunity to become and feels the absence of a mistress of the house as he struggles to manage his niece and servants. Angelica maintains a dysfunctional relationship with her ‘keeper’ Mrs Frost, the woman who first encouraged her to enter her current profession, and who as it turns out was not as kind or trustworthy a friend as Angelica believed.

The secondary characters also share this concern. Sukie, Mr Hancock’s niece, is constantly on her guard as to being replaced or shunted out of the household when she is no longer useful. Mrs Chappell is losing her influence in society. Polly is dissatisfied with her social position.

Crucially, it is women, and how they choose to exert their power, who emerge as the stabilising force to this chaos.

It is Sukie who decides to persevere with the exhibition of the first mermaid when her uncle loses heart, while it is Angelica, not the perpetually timid Mr Hancock, who confronts Sukie’s mother and confirms her place within the household. There is a vision at the end of the novel of a kind of harmony, wrought by Angelica through a second mermaid party with a suitably “amphibious” guest-list of ex-prostitutes and merchants and tradespeople, upper-class and middle-class. Although, as it is wryly noted, the guests still “succeed in speaking to nobody outside their own sort”.

Angelica also performs the most important act of the novel, in deciding to liberate the second mermaid from its imprisonment. Her initial plan is to display it- a forced humiliation- but instead she chooses to treat it with empathy and compassion, asking “What trapped creature does not strike out?”. She will not use her power over the mermaid to degrade it, as she was once degraded by those in power:

“She balances the bucket on her shoulder, tips it gently, and pours it out in a long unbroken stream, so that at the end the water closes in a perfect ‘O’, and one single drop leaps up into the air.

‘And so it is done,’ she says.”

Thus, the cycle of pain is broken not through domination, but through courage and kindness and decisive action taken by a woman.

We get a version of the happy ending, which is not the image of idyllic perfection which typically closes a fairy-tale. Instead of happily ever after, there is hope of love after marriage, the miscarriage of a baby, and the dampening of Sukie’s spirit (hopefully not permanently).

But something good, a little pocket of it, has been created, because in a modern age “things that are wrought may be quite as extraordinary as those that are found.” A mermaid may appear to be a magical discovery, but is it any more rare and wonderful than finding long-lasting and quiet satisfaction and happiness in life? As Berman so movingly expresses, the daily routine of life may not be glamorous or perfect, but it is “infinitely joyous and beautiful” and as Gowar’s characters find, “infinitely precarious and fragile”.

Ghosts of an unhappy past will always surround us, but we can, and we must, learn to live with them.

…

I originally wrote this as part of my university coursework (hence the references to Berman). Hope you enjoyed it!

Quotations: The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock by Imogen Hermes Gowar

I love the cover of this book, but I’m still not sure if I want to read it or not

LikeLiked by 1 person

I would definitely recommend it, though it is quite slow paced. The cover is gorgeous 😍

LikeLike